Buenos Aires, April 25th, 2003.

The Shock of the New

An Interview with Colectivo Situaciones

By Marina Sitrin

The social movements that exploded in Argentina in December 2001 not only transformed the fabric of Argentine society but also issued a ringing testimony to the possibility of a genuinely democratic alternative to global capital. The whole world was watching.

For all the theories about what constitutes and how to make revolutions, in essence they are nothing more than ordinary people coming together to discuss and fight for social possibilities that were previously beyond the horizon of historical possibilities. At its root, it is about the creation of new dialogues.

Colectivo Situaciones is a radical collective in Buenos Aires dedicated to stimulating these dialogues. They have tried to facilitate the most far-reaching aspects of the discussions that have unfolded among the social conflicts in Argentina through their books, which are (literally) structured as dialogues.

These discussions transcend national boundaries. Marina Sitrin interviewed Colectivo Situaciones while in Argentina this spring, where she was working on her forthcoming book, which will be a collection of interviews exploring the Argentine uprising through the political and personal experiences of those involved. She was awarded a grant by the IAS in July 2003 in support of her work (see “Grants Awarded” for more information).

Reprinted here is an excerpt from her interview. This interview explores the difficulty of creating concepts adequate to the new Argentine social movements, some of the political vocabulary that has emerged from these movements, and the meaning of engaged theoretical work. It was conducted in Buenos Aires on April 25th, 2003.

Chuck Morse

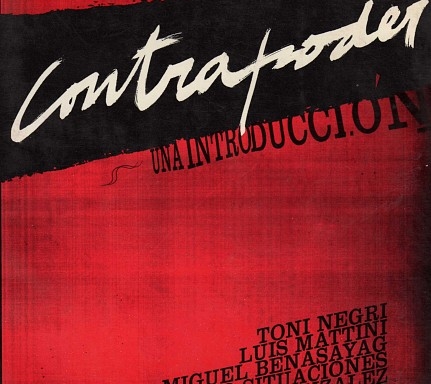

Colectivo Situaciones emerged from Argentina’s radical student milieu in the mid 1990s and, since then, have developed a long track record of intervention in Argentine social movements. Their books are dialogues with the unemployed workers movement, explorations of the question of power and tactics of struggle, and conversations about how to think about revolution today.

Their radical views pertain to practice as much as theory. They are genuinely a collective and all of their projects are collectively produced. Presently, in addition to their publishing work, they are also working in a collectively run, alternative school.

In a note printed on the back of many of their books, they describe their work as follows:

[We] intend to offer an internal reading of struggles, a phenomenology (a genealogy), not an “objective” description. It is only in this way that thought assumes a creative, affirmative function, and stops being a mere reproduction of the present. And only in this fidelity with the immanence of thought is it a real, dynamic contribution, which is totally contrary to a project or scheme that pigeonholes and overwhelms practice.

More information can be found on their website at www.situaciones.org. The IAS awarded a grant to Nate Holdren in July 2003 for a translation of their book 19 and 20: Notes for the New Social Protagonism (see “Grants Awarded” for more information).

Radicals have often been criticized for imposing ideas and dogmas upon events instead of attending to their real nuances and complexities. Colectivo Situaciones has tried to overcome the strategic and intellectual impasse that this creates by advancing a contextually sensitive approach to the world. I asked them to explain their method and to give background on their collective.

At a particular moment we began to see what, for us, was a fundamental lack of options for left libertarians and autonomists in general. We began to feel very dissatisfied with the discourse on the Left—of the activists, the intellectuals, the artists, and the theoreticians—and began to ask ourselves if we should put our energy in the investigation of the fundamentals of an emancipatory theory and practice. Since that day, we have continued pursuing that same question and, since that day, things have been appearing, like Zapatismo. Certain people also began appearing in the theoretical camp, asking very radical questions, and they influenced us a lot. We studied them, got to know them, and exchanged a great deal. Also, in Argentina there began to emerge very radical practices that also questioned all of this, carried out by people who were also searching.

During this process, certain key ideas kept appearing to us that we decided to develop and see where they would lead. One of the ideas that we came across was that, as much potential as thought and practice have, they cannot reach their full potential if not based in a concrete situation. In some respects, this is pretty evident, or should be, but normally developing a thought or practice within a situation is not easy. We decided to immerse ourselves in this work. We do not think that situations can be created, and this is the difference that we have with the Situationists of Europe in the late 50s and early 60s, who believed that a situation could be created, and who tried to create situations. We think not: situations are to be entered or taken on, but cannot not be invented by ones’ own will.

This gives rise to what Gilles Deleuze said: “creation as resistance, resistance as creation.” We consider our own collective an experience of resistance and creation, to create resisting in the area of thought, linked to practice.

However, for us it is difficult to speak in general terms. When you say “Piquetero movement,” you are creating a homogeneity—an equality of circumstances, of characteristics, of a quantity of things—that in reality does not exist. This has to be seen in context. We work in concrete experiences and part of our work consists of attempting not to make generalizations. We believe there are points, or practical hypotheses, that develop in distinct moments, and that each movement, each concrete situation, develops in a particular, determined form. For example, the influence that Zapatismo has had is evident as an inspiration, but to say that the Argentine movement is the Zapatista movement would be an absurd generalization. What we are working to make more general is the concept of “new social protagonism.” This concept is not something that lumps together various phenomena, but is rather a concrete way of working in specific contexts, that we believe will advance and radicalize the question of what social change means today. Not everyone has the same work, the same answers, nor develops in the same way. But, shared is the new social protagonism’s radicalism in posing these questions as well as bringing forward its practice. Generalizing is difficult because it hides the complexity of concrete situations.

Through the Argentine uprising many people began to see themselves as social actors, as protagonists, in way that they had not previously. I asked Colectivo Situaciones how such a rapid radical transformation could take place and how it could be so widespread.

The parties were a huge fraud for all the people, for everyone in general, but doubly so for those that had an emancipatory perspective. In addition, it is evident that the Argentine state failed, not only the political parties. The state in default, totally captured by the mafias, a state that neither manages to regulate nor generate mediations in society, ended up destroying the idea, so strongly installed in Argentina, that everything had to pass through the state. Thus, between this and the global militancy that was developing, the ideology of the network, plus the presence of the Internet and the new technologies, the new forms of the organization of work… these things reinforced the ideology of horizontalism. This also coincides with the most important ideas of the new social protagonism: Decisions made by all; the lack of leaders; the idea of liberty; that no one is subordinated to another; that each one has to assume within him or herself responsibility for what is decided; the idea that it is important to struggle in all dimensions; that struggle doesn’t take place in one privileged location; the idea that we organize ourselves according to concrete problems; the idea that it is not necessary to construct one organization for all, but that organization is multiple; that there are many ways to organize oneself according to the level of conflict one confronts; the idea that there is not one dogma or ideology, but rather open thinking and many possibilities. It also has to do with the crisis of Marxism, which was such a heavy philosophical and political doctrine in the 60s and 70s. Also, in Argentina, the collapse of the military dictatorship produced very strong experiences, such as the Madres de Plaza de Mayo, who showed early on that political parties are not an efficient tool for concrete, radical struggles.

But now there is an ambivalence, because there are many people doing very important things at the level of this new social protagonism: in a school, a hospital, a group of artists, a group of people creating theory; and perhaps the notion of horizontalism is not the most important for them. For example, we are working in a school where, of course, everyone makes decisions together, but not because the participants adhere to a horizontalist ideology, but rather because the situation itself makes us equals in the face of problems.

Thus, it seems there is a distinction. Many times, in asambleas, we see a discussion of horizontalism as a political identity. We say that it is not about the theme of horizontalism, but about political identity . We say that one is not organized according to pure imaginaries—I am a revolutionary, a communist, a Peronist, an autonomist… but rather one works on concrete problems. For us this is where nuclei of greater power exist: in some asambleas, neighbors, without anyone convoking them, without a political power, with any political representation, start discussing what it means to say that they want to play a leading role in something; what it means to take charge themselves, that the state is not going to take responsibility for them, that society is unraveled, is disarmed, disintegrates if there is not the production of new values by the base. Thus, this self-organization is very important from this point of view. Previously there were the piqueteros , who have a much longer history than the asambleas , and discovered all of this before.

The word “horizontalism” is part of the new political vocabulary that has emerged out of the Argentine movements. It is used by many in these movements—from the piqueteros and asambleas to those who have occupied factories—to speak of the political relationships being formed. I asked Colectivo Situaciones to share their thoughts on the meaning and usage of this word.

There is a question of leadership. The politics of horizontalism, in the most moral sense, supposes that when a group of people exercise leadership or are very active or tend to be organizers, that there is a danger of verticalism or institutionalization. To us, it seems that this can only be known in the context. What happens if every time a person talks a lot or is very active that person is accused of being an institution that restrains the movement? To us it seems that this reveals a significant exteriority of the situation and a big moralization.

Many times, in a simple perspective, it would seem that there is horizontalism when everyone speaks equally, because nobody does more than the others. But it is necessary to see that often subjugation is not the subjugation of a person: it can also be the subjugation of an ideal, or subjugation in the impossibility of doing things. There is the impotence and sadness that can exist in forms that appear horizontal from the outside.

Thus, we don’t celebrate the fact that there are asambleas in the abstract. Many asambleas don’t interest us, because even though everyone speaks, there isn’t really an opening, there isn’t really active power ( potencia) . Whereas other groups that are accused of not being sufficiently horizontal are creating possibilities and hypotheses and changing the lives of the persons so much that they generate a very strong attraction and very strong power. For example, think of Zapatismo . As in Zapatismo , as in some MTD (Movimiento de trabajadores desocupados/Unemployed Workers’ Movement)—like the MTD of Solano—there are people who are the most horizontal of the horizontals that question if there is sufficient horizontalism. But, to us it seems unnecessary to try to make an experience that functions a model for the majority.

Horizontalism is a tool of counter-power when it is a question—power is socialized, it is democratized, it is the power of all—but horizontalism is a tool of power when it is a response, when it the ends the search, when it shuts down all questions. Horizontalism is the norm of the multiplicity and the power of the people who are different, not of those who follow the conventional. The risk is that horizontalism shuts you up and becomes a new ideology that aborts experimentation. That is the risk.

Although Colectivo Situaciones’ books are highly theoretical—and often difficult reading for native Spanish speakers—they are decidedly anti-academic and try to produce a militant, engaged theory. I asked them to explain their approach to me.

Something that interests us is the struggle against academic thought, against classical academic research. It is often said that militant investigation is good, because it manages to show things closely, very internally, but that it is not good because it lacks distance and does not permit objectivity. We are developing an idea that is precisely the contrary. [We believe that] only by adopting a very defined perspective is it possible to comprehend the complexities and tensions of a situation. What we have is a position of work that demands deep practical engagement: it implies a lot of time, a lot intensity, a lot of study, and a high level of sensitivity. For us, it is not an obstacle to knowledge, but the only form that goes with the development of truly complex thought. Our experience is that, in the end, the Argentine academy—not only in the university, but also in the mass media and arts—tries to grasp what is happening without being engaged or fully developing ideas. We see very clearly the difference between us and them. Our work functions in exactly the opposition sense….

Translated from Spanish by Chuck Morse and Marina Sitrin